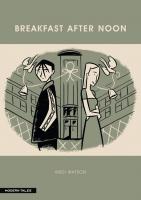

Seit über zehn Jahren veröffentlicht der Engländer Andi Watson seine Graphic Novels bei diversen US-Verlagen, doch erst im letzten Jahr erschien sein erster Comic auf deutsch: Modern Tales veröffentlichte Breakfast After Noon über ein junges Paar, das gerade seine Hochzeit plant, als der angehende Bräutigam arbeitslos wird.

Seit über zehn Jahren veröffentlicht der Engländer Andi Watson seine Graphic Novels bei diversen US-Verlagen, doch erst im letzten Jahr erschien sein erster Comic auf deutsch: Modern Tales veröffentlichte Breakfast After Noon über ein junges Paar, das gerade seine Hochzeit plant, als der angehende Bräutigam arbeitslos wird.

Watson ist ein sehr vielseitiger Künstler, der sich nicht auf ein bestimmtes Genre beschränkt und sich auch zeichnerisch für jedes seiner Projekte verändert, wobei er trotzdem einen unverwechselbaren Stil entwickelt hat.

Comicgate-Redakteur Thomas Kögel traf Andi Watson auf der Frankfurter Buchmesse 2006 (Ja, das ist ein Jahr her! Sorry!) zum Interview. Ein Schwerpunkt des Gesprächs lag auf dem Spannungsfeld zwischen Kunst und Kommerz bzw. zwischen Auftragsarbeiten und eigenen kreativen Schöpfungen.

Wir bieten Euch das Interview im Original auf Englisch und übersetzt auf Deutsch an.

Für das Originalinterview bitte hier klicken – please click here for the English version.

Andi Watson, geboren 1969 im englischen Yorkshire, macht seit den frühen 90er jahren Comics. Seine Abschlussarbeit für das Graphikdesign-Studium war der Comic Samurai Jam, den er selbst veröffentlichte. Dadurch wurde der US-Verlag Slave Labor Graphics auf ihn aufmerksam, für den er bis heute diverse Comics geschrieben und gezeichnet hat (z.B. Skeleton Key und Slow News Day).

Außerdem schuf Watson Miniserien und Graphic Novels für Oni Press (Breakfast After Noon, Love Fights, Little Star) und das neue DC-Label Minx (Clubbing). Aktuell erscheint bei Image Comics Glister, ….

Neben seinen recht persönlichen Arbeiten im Indie-Bereich arbeitet Watson auch als Autor für Mainstream-Comics wie z.B. Buffy the Vampire Slayer oder Star Wars (Dark Horse).

CG: Breakfast After Noon ist dein erster Comic, der auf deutsch veröffentlicht wird. Dein Verleger Stefan Heitzmann schreibt auf der Verlags-Website , dass das deine beste Arbeit sei. Siehst du das auch so?

AW: Ääähmm… nein. Ich glaube, die letzte Arbeit findet man immer am besten, aber Breakfast After Noon ist, vom Aufbau der Geschichte her, am klassischsten strukturiert. Ich kann also verstehen, dass das befriedigender zu lesen ist. Little Star dagegen, das ich kürzlich abgeschlossen habe, war nicht so gründlich strukturiert. Das Ende war viel offener. Die Charaktere lernen nicht unbedingt etwas, es gibt keine Lektion am Ende, während es in Breakfast After Noon eine Art moralischen Subtext gibt.

CG: Aber es ist ein guter Einstiegspunkt in dein Werk, oder?

AW: Ja, ich denke schon. Es ist wahrscheinlich der beste Startpunkt, und von da aus geht es hoffentlich nicht bergab (lacht).

CG: Wenn du dir aussuchen könntest, was deine nächste Veröffentlichung in Deutschland werden soll, was würdest du wählen?

AW: Vielleicht sowas wie Slow News Day, weil das auch eher traditionell aufgebaut ist, eher wie ein Film in drei Akten, und es hat ein Happy End. Es gehört zu einem sehr zugänglichen Genre, es ist eine romantische Komödie mit Bürokram. Ich bin mir nicht sicher, wie gut sich das auf Deutschland anwenden lässt, mit der Lokalzeitung und so, inwiefern das hier Sinn ergibt. Aber wenn ich zum Beispiel an Little Star denke, da weiß ich, dass die Unterschiede zwischen den Geschlechtern in Deutschland etwas anders sind. Die Mütter bleiben in der Regel zuhause und die Väter gehen arbeiten. Also keine Ahnung, wie das zur deutschen Kultur passt. Aber ich glaube, wenn die Deutschen Hollywoodfilme gewöhnt sind und sie mögen, dann wäre etwas wie Slow News Day ein guter nächster Schritt.

[Anm. d. Red.: Inzwischen hat Modern Tales Little Star als zweiten Comic von Andi Watson auf deutsch veröffentlicht.]

CG: A propos Happy End: Breakfast After Noon hat so eine Art Happy End, kein echtes Hollywood-Ende, aber auch kein trauriges. Als ich es gelesen habe, habe ich mich gefragt, ob du vielleicht auch erwägt hast, der Geschichte ein weniger glückliches Ende zu geben?

CG: A propos Happy End: Breakfast After Noon hat so eine Art Happy End, kein echtes Hollywood-Ende, aber auch kein trauriges. Als ich es gelesen habe, habe ich mich gefragt, ob du vielleicht auch erwägt hast, der Geschichte ein weniger glückliches Ende zu geben?

AW: Ich denke, der springende Punkt dieser Geschichte ist, dass Rob einen Abstieg durchmacht und sich selber wieder hochziehen muss. Ich meine, wenn es mit ihm abwärts geht, und dann geht's noch weiter abwärts und das ist dann das Ende, dann ist da nicht viel emotionaler Gewinn für den Leser. Das Ende ist eine Art Auflösung, obwohl man nicht genau weiß, wie stabil ihre Beziehung letztlich ist. Wenn Rob erfährt, dass ein Kind unterwegs it, wird er davon wachgerüttelt und er wird erwachsen. Ich dachte nicht: „Wenn ich ein trauriges Ende schreibe, wäre das Buch weniger erfolgreich“, es war einfach die Art, wie die Figuren gestrickt sind: Rob lernt nicht direkt eine Lektion, aber im Verlauf der Handlung verändert er sich. Wenn er am Anfang selbstsüchtig und am Ende noch selbstsüchtiger wäre, dann gäbe es keine echte Geschichte, kein Drama, keinen Wendepunkt. Wenn er aber eine zeitlang ein egoistischer Depp ist und dann die Konsequenzen seines Verhaltens erkennt, ergibt das ein interessanteres Buch, denke ich.

CG: Du lebst in Großbritannien, machst aber den Großteil deiner Arbeit für amerikanische Verlage. Gibt es eigentlich eine nennenswerte Comicszene in England? Abgesehen von 2000 A.D., was das einzige ist, was ich kenne.

AW: Ja, das ist es so ziemlich. Es gibt einige Kleinverleger, Fanzines und Undergroundcomics. Aber wenn du als Comiczeichner oder -autor Geld verdienen musst, musst du in die USA gehen, für DC oder Marvel arbeiten und in der Regel Superheldencomics machen. Das ist der Weg für die meisten, aber so wie sich Graphic Novels gerade entwickeln, ändern sich die Dinge. Verlage wie Walker Books fangen an, Comicadaptionen von Kinderbüchern wie Stormbreaker herauszubringen. Ich denke, sie sehen einen Wachstumsmarkt und vielleicht wird es in England aufwärts gehen. Ich hoffe, dass die Verlage in britische Kreative investieren werden. Viele Verlage wie Jonathan Cape bringen einfach Neuveröffentlichungen von amerikanischen Autoren. Das verstehe ich nicht. Man will doch seinen eigenen heimischen Nachwuchs heranziehen und Leute, die über die eigene Kultur sprechen. Klar, sowas wie Palestine von Joe Sacco ist ein tolles Buch, aber ich verstehe nicht, warum man das unbedingt von einem britischen Verlag kaufen muss. Wenn die Leute es haben wollen, bekommen sie es sowieso. Ich wünschte, es würde mehr Geld im eigenen Land ausgegeben werden, so dass sich eine eigene britische Comickultur entwickeln kann.

CG: Gibt es bei der Arbeit für amerikanische Verlage Probleme, wenn sich alles quer über den Atlantik abspielt? Vermisst man persönliche Kontakte, hast du überhaupt persönlichen Kontakt zu deinen Verlagen?

AW: Bevor ich Vater wurde, reiste ich jedes Jahr zu den amerikanischen Conventions. Ich merkte, dass das wirklich was bringt. Denn wenn man sich ein paar Jahre nicht sehen lässt, dann gerät man aus dem Blickfeld und existiert nicht mehr. Die Arbeit selber funktioniert prima, alles per E-Mail und FTP, heutzutage ist sowieso alles digital. Man lädt seine Sachen hoch oder runter, da gibt es kein Problem. Aber ich glaube, persönliche Präsenz bei Conventions und Messen bringt wesentlich mehr als immer nur E-Mails zu senden. Man muss da immer wieder rüber. Selbst wenn es dich erstmal Geld kostet, es ist eine Langzeit-Investition. Man sagt „Hey, ich lebe noch, mich gibt's noch, ich arbeite noch“, anstatt einfach zu verschwinden. Die Amerikaner kommen nämlich nicht zu Conventions nach England. Dort ist die Szene sehr klein, so dass es für sie finanziell nicht sinnvoll ist. Da musst du schon selbst zu denen kommen.

AW: Bevor ich Vater wurde, reiste ich jedes Jahr zu den amerikanischen Conventions. Ich merkte, dass das wirklich was bringt. Denn wenn man sich ein paar Jahre nicht sehen lässt, dann gerät man aus dem Blickfeld und existiert nicht mehr. Die Arbeit selber funktioniert prima, alles per E-Mail und FTP, heutzutage ist sowieso alles digital. Man lädt seine Sachen hoch oder runter, da gibt es kein Problem. Aber ich glaube, persönliche Präsenz bei Conventions und Messen bringt wesentlich mehr als immer nur E-Mails zu senden. Man muss da immer wieder rüber. Selbst wenn es dich erstmal Geld kostet, es ist eine Langzeit-Investition. Man sagt „Hey, ich lebe noch, mich gibt's noch, ich arbeite noch“, anstatt einfach zu verschwinden. Die Amerikaner kommen nämlich nicht zu Conventions nach England. Dort ist die Szene sehr klein, so dass es für sie finanziell nicht sinnvoll ist. Da musst du schon selbst zu denen kommen.

CG: Kannst du uns etwas über die Unterschiede zwischen der Arbeit an Lizenzcomics — du hast u.a. Skripts für Buffy– und Star-Wars-Comics geschrieben — und deinen eigenen Schöpfungen erzählen? Ich denke, da gibt es große Unterschiede…

AW: Bei meinen eigenen Comics bin ich bis zu einem gewissen Grad mein eigener Boss. Wobei man trotzdem immer noch Deadlines einhalten muss und sowas. Bei der Arbeit an Buffy, oder an Namor, das ich für Marvel geschrieben habe, arbeitet man für einen Boss, der eine Erwartung hat, was dabei rauskommen soll. Im Grunde hast du zu tun, was man dir sagt. Man kann nicht unbedingt seine Stärken ausspielen — Namor z.B. war ein Action-Abenteuer-Comic für Jungs, und trotzdem wollten sie auch noch eine Romanze einbauen, aber das hat einfach nicht gepasst.

Es ist schwer und in kreativer Hinsicht wird man dafür nicht belohnt, aber man wird bezahlt. Das ist der Hauptgrund, es zu machen. Die bittere Wahrheit ist, dass man nur von regelmäßigen, monatlichen Serien richtig leben kann. Den Rest der Zeit muss man versuchen, die persönlichen Arbeiten mit den kommerziellen unter einen Hut zu bringen.

CG: Es gibt da ein Zitat vom Regisseur Steven Soderbergh, der sinngemäß sagte: „Einen mach ich für sie [die Hollywood-Studios], und dann wieder einen für mich“. Teilst du diese Einstellung?

CG: Es gibt da ein Zitat vom Regisseur Steven Soderbergh, der sinngemäß sagte: „Einen mach ich für sie [die Hollywood-Studios], und dann wieder einen für mich“. Teilst du diese Einstellung?

AW: Ja. Ich meine ich würde lieber ständig „einen für mich“ machen, aber das ist nicht immer möglich. Man muss den Ball am Rollen halten und sicherstellen, dass man immer wieder zu seinen eigenen Arbeiten zurückkommen und an eigenen Ideen arbeiten kann. „Work for hire“ ist sehr verführerisch, es ist ziemlich angenehm, man wird regelmäßig bezahlt und so weiter. Es kann leicht passieren, dass man da reinfällt und Sachen für andere raushaut, die einem selbst nichts bedeuten und die nichts Wert sind. Man füllt halt einfach Lücken im Veröffentlichungskalender…

Es ist also ein ständiger Kampf, wenn man versucht Geld zu verdienen und sich selber auf eine erfüllende Art auszudrücken.

CG: Aber für dich scheint diese Balance zu funktionieren…

AW: Im Großen und Ganzen ja. Ich sag's nochmal, man muss zu den Conventions gehen und die Leute persönlich treffen. Und man muss zumindest so tun, als sei man total begeistert davon, Buffy the Vampire Slayer zu schreiben, auch wenn es nicht stimmt. Man muss offen für diese Art von Arbeit bleiben. Ich würde auch gerne Romane oder sowas schreiben, aber damit lässt sich auch kaum Geld verdienen, also muss ich weiterhin zu Marvel und DC gehen und um Arbeit betteln. Das macht keinen Spaß, muss aber sein.

CG: Auf dem Weg nach Frankfurt habe ich deine Graphic Novel Geisha gelesen. Dort geht es im Subtext sehr viel um das Thema „Kunst oder Kommerz“. Das scheint ein recht wichtiges Thema für dich zu sein.

AW: Ja, das ist wirklich ein sehr interessantes Thema für mich. In einem anderen Comic von mir, Love Fights, der bisher nur ins Spanische übersetzt wurde, leben die Figuren in einer Welt, in der es Superhelden gibt, die ein Copyright auf ihr Outfit besitzen. Es ist eine Welt, in der Kunst und Kommerz zusammenprallen, was ich wirklich interessant finde. Das kommt bei mir immer wieder. Da steckt eine Menge Drama drin.

AW: Ja, das ist wirklich ein sehr interessantes Thema für mich. In einem anderen Comic von mir, Love Fights, der bisher nur ins Spanische übersetzt wurde, leben die Figuren in einer Welt, in der es Superhelden gibt, die ein Copyright auf ihr Outfit besitzen. Es ist eine Welt, in der Kunst und Kommerz zusammenprallen, was ich wirklich interessant finde. Das kommt bei mir immer wieder. Da steckt eine Menge Drama drin.

In Slow News Day ist es das gleiche: Will man für eine kleine Zeitung mit einer kleinen Leserschaft arbeiten oder für ein Millionenpublikum im Fernsehen? Das ist eine tolle Konfliktquelle für Charaktere, die versuchen, sich selbst treu zu bleiben. Es wird immer bedeutsamer, denke ich, wenn man sich ansieht, wie stark die Medien globalisiert werden.

Eine Serie wie Friends verkauft sich auf vielen Märkten in der ganzen Welt. Aber dadurch wächst auch der Druck, dass es nicht zu spezifisch oder ortsbezogen sein darf, damit die Zuschauer in aller Welt es verstehen. Das ist ein interessantes Thema, und das taucht auch in Breakfast After Noon auf: Die Hauptfigur, Rob, arbeitet für eine britische Keramikfirma, aber sein Kaffeservice kauft er bei Ikea. Die Leute machen sich zu wenig Gedanken darüber, dass ihr Kaufverhalten Auswirkungen auf die Welt um sie herum hat, und im Prinzip trägt Rob selber dazu bei, dass er seinen Job verliert.

CG: Du zeichnest und schreibst ja nicht nur deine eigenen Comics, sondern schreibst auch für andere Zeichner, wie bei Paris (mit Simon Gane, SLG Publishing). Was ist der Unterschied, wenn man für jemand anderen schreibt?

CG: Du zeichnest und schreibst ja nicht nur deine eigenen Comics, sondern schreibst auch für andere Zeichner, wie bei Paris (mit Simon Gane, SLG Publishing). Was ist der Unterschied, wenn man für jemand anderen schreibt?

AW: Für andere Künstler zu schreiben, ist sehr befriedigend, wenn man ihre Stärken ausspielt. Paris z.B. hat nur sehr wenige Panels pro Seite und es wird mehr Wert auf Details gelegt, wie Architektur oder küssende Mädchen. Mich selbst interessierte das nicht allzusehr, aber Simon wollte unbedingt sowas machen, also gab er mir einen „Einkaufszettel“ mit Dingen, die er zeichnen wollte. Den nahm ich und baute diese Dinge in die Geschichte ein. Und ja, es ist fantastisch, wenn die Seiten von Simon zurückkommen mit diesen wunderschönen Szenen in Paris, das ist einfach eine tolle Erfahrung. Das ist das erste Mal, dass ich wirklich diese Begeisterung spüre. Zuvor waren meine Autoren-Jobs nur „work for hire“ und nichts, womit ich mich persönlich verbunden fühlte.

CG: Hast du mal nach einem Skript eines anderen Autoren gezeichnet?

AW: Äääähm… (überlegt) Ja, nur Kleinigkeiten, nichts großes. Zum Beispiel in diesem DC-Comic Bizarro, einer Sammlung von Kurzgeschichten, dafür habe ich was von Evan Dorkin und ein paar anderen gezeichnet. Das ist schon interessant, denn Autoren bringen dich dazu, Sachen zu zeichnen, die du normalerweise nicht zeichnest. Wenn ich einen Comic mit einem Verkehrsstau zeichnen müsste, wäre das eine echte Herausforderung, denn ich hasse es, Autos zu zeichnen und bin auch nicht sehr gut darin. Man wird also in Gefilde gestoßen, in die man sich sonst nicht hineinwagt, und das ist gut.

Aber bei Comics sind das Tempo und das Seitenlayout derart wichtig, dass es selten eine echte Verbindung [zwischen Autor und Zeichner] gibt, außer es sind zwei Leute, die wirklich gleich ticken und die gleichen Interessen haben. Bei Paris ist das der Fall, Simon und ich mochten wirklich die gleichen Sachen: Kunst und Ingres und klassische Malerei und all das Zeug. Wir waren wirklich einer Meinung. In diesem Fall klappte es also, aber ich weiß nicht, ob es Spaß machen würde, eine Graphic Novel über einen Stau zu zeichnen. Nur Autos über Autos, verstehst du? Das kann schon interessant sein, aber ich arbeite lieber an meinem eigenen Kram, wann immer es geht.

CG: Wo wir grade beim Zeichnen sind: Fast alle deine Comics sind in schwarz-weiß. Das kann finanzielle oder auch künstlerische Gründe haben. Wie ist das bei dir?

AW: Schwarz-weiß ist viel direkter und es braucht weniger Zeit. Und wenn man Erfahrung hat, kann man mit schwarz-weiß die gleichen Effekte erzielen wie mit Farbe. Und natürlich gibt es noch den finanziellen Aspekt. Mit Farben kann man den emotionalen Ton eines einzelnen Bildes beeinflussen, aber dann muss man auch alle Panels auf einer Seite im Auge behalten und in der Balance halten. Das ist viel mehr Arbeit, da steckt viel mehr drin.

AW: Schwarz-weiß ist viel direkter und es braucht weniger Zeit. Und wenn man Erfahrung hat, kann man mit schwarz-weiß die gleichen Effekte erzielen wie mit Farbe. Und natürlich gibt es noch den finanziellen Aspekt. Mit Farben kann man den emotionalen Ton eines einzelnen Bildes beeinflussen, aber dann muss man auch alle Panels auf einer Seite im Auge behalten und in der Balance halten. Das ist viel mehr Arbeit, da steckt viel mehr drin.

Im Idealfall, wenn ich etwas farbiges machen würde, würde ich mit einem wirklich guten Koloristen arbeiten wollen, mit dem ich auf der gleichen Wellenlänge bin. Sowas wie Hellboy, was wirklich wunderschön koloriert ist. Die Kolorierung ist hier ein Element des Storytelling. Mike Mignola arbeitet offensichtlich in schwarz-weiß, aber er hat die Farben die ganze Zeit im Kopf und weiß, wie es später auf der Seite aussehen wird. Ich bewundere die Art, wie das funktioniert, aber es schüchtert mich auch ein bisschen ein, weil es so schwierig ist.

Ich bin es gewohnt, in schwarz-weiß zu arbeiten, und bei Farbe muss man einfach mit viel mehr Dingen jonglieren, wenn man eine Seite zusammenbaut. Es ist natürlich toll, verschiedene emotionale Effekte herauszuholen, aber das bedeutet auch weitere Stunden am Schreibtisch, vor dem Computer. Aber ich denke man kann solche Effekte auch in schwarz-weiß erzielen und es dauert einfach nicht so lange, was immer ein Vorteil ist.

CG: Du hast Hellboy angesprochen. Ironischerweise veröffentlicht der deutsche Verlag [Cross Cult] die Hellboy-Comics in schwarz-weiß, weil man dort der Ansicht ist, das sähe besser aus und Mignola sie eigentlich in schwarz-weiß zeichnet. Und alle, naja nicht alle, aber die meisten Leser sind begeistert davon, sogar Mignola selbst und [der US-Verlag] Dark Horse sagen, dass es toll aussieht. Ich glaube, bei Hellboy funktioniert beides.

AW: Ja, auf jeden Fall. Ich habe seine ersten Hellboy-Episoden in Dark Horse Presents gesehen, die waren schwarz-weiß und sind fantastisch. Mike Mignola weiß einfach, wie man ein Panel ins Gleichgewicht bringt und wie man tiefes Schwarz gegen weiße Flächen einsetzt. Darin ist er brilliant. Ja, ich würde auch beides kaufen.

CG: Schau's dir an, der Stand von Cross Cult ist direkt gegenüber vom Modern-Tales-Stand…

AW: Oh toll! Dann will ich eine Ausgabe.

CG: Meine letzte Frage hat mit Manga zu tun. Manga gehört ja auch zu deinen Einflüssen, vor allem bei deinen frühen Arbeiten. Hier in Deutschland haben wir einen sehr stark getrennten Markt. Die Mangafans auf der einen Seite und die Anhänger westlicher Comics auf der anderen. Einige Verlage machen zwar beides, aber die meisten Leser lesen entweder nur Manga oder westliche Comics. Alles ist zweigeteilt, und in den USA und im UK wird es nicht viel anders sein. Ich finde das furchtbar schade, schließlich geht es immer ums Geschichtenerzählen in Form von sequentieller Kunst. Was denkst du, wie ließe sich das ändern?

AW: Ich denke, es wird sich mit der Zeit ändern. Es wird nicht sofort geschehen, aber die Kids, die jetzt Mangas lieben, werden irgendwann eigene Comics zeichnen wollen. Einige werden sklavisch Manga-Stilen folgen, aber ich glaube, viele werden verschiedene Elemente aufgreifen, aus westlichen Comics, aus der Illustration usw. Und mit der Zeit, hoffe ich, wird das nicht mehr so stark getrennt sein und zusammenwachsen. In Frankreich geht das schon los, da gibt es eine Bewegung, die gezielt mit beiden Elementen arbeitet. Für mich ist das alles visuelles Geschichtenerzählen. Der Comic ist wirklich eine universelle Sprache.

Ich kann verstehen, wenn junge Leser ziemlich hardcore sind. Das ist doch wie bei der Musik: Du hörst Heavy Metal und sonst nichts, oder du hörst ausschließlich Punkrock. Wenn die Leute älter werden, werden sie hoffentlich nicht mehr so verklemmt auf Labels, aufs Dazugehören achten. Aber egal, ich bediene mich gerne bei Bandes Dessinées und bei Manga und bei Superheldencomics. Filme, Romane, bildende Kunst, das alles steht mir zur Verfügung, das alles kann ich frei verwenden und mich davon inspirieren lassen.

Ich kann verstehen, wenn junge Leser ziemlich hardcore sind. Das ist doch wie bei der Musik: Du hörst Heavy Metal und sonst nichts, oder du hörst ausschließlich Punkrock. Wenn die Leute älter werden, werden sie hoffentlich nicht mehr so verklemmt auf Labels, aufs Dazugehören achten. Aber egal, ich bediene mich gerne bei Bandes Dessinées und bei Manga und bei Superheldencomics. Filme, Romane, bildende Kunst, das alles steht mir zur Verfügung, das alles kann ich frei verwenden und mich davon inspirieren lassen.

CG: Was man deinen Comics auch ansieht…

AW: Danke! Ja, ich meine, man muss einfach nur die Augen offenhalten. Ansonsten bleibt man für immer in einem Stil hängen und verliert die Energie und den Enthusiasmus. Man muss dauerhaft offen für Neues sein, sonst wird man nur alt und langweilig (lacht).

![]()

andiwatson.biz: Offizielle Website mit Arbeitsproben, Blog und Interview-Links

Andi Watson bei Modern Tales: Biographie und Leseproben

Andi Watson bei Oni Press : Infos und Leseproben

Andi Watson bei SLG Publishing: Infos im SLG-Blog

Comicgate-Rezension von Breakfast After Noon

Bildquellen: Andi Watson, slgcomic.com, onipress.com, darkhorse.com, modern-tales.de. Fotos: Thomas Kögel

{mospagebreak title=Interview with Andi Watson (English)}

Englishman Andi Watson is wrting and drawing Comics for various American publishers for more than ten years, but it wasn't until 2006 that his first German translation came out: Breakfast After Noon was published by the Label Modern Tales, a comic about a young couple which ist planning their wedding, as the groom loses his job.

Watson is a very versatile artist whose work isn't restricted to a certain genre and whose style changes from project to project, although developing a distinctive personal touch.

Comicgate's editor Thomas Kögel met Andi Watson at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2006 (Yes, that was one year ago! I know I'm late, sorry!) for an interview. Among other things, they talked about the conflicts between art and commerce, between doing work-for-hire and working for one's own creative visions.

Andi Watson, born in 1969 in Yorkshire, England, started creating comics in the earls nineties.

geboren 1969 im englischen Yorkshire, macht seit den frühen 90er Jahren Comics. He made his final degree as a graphic design student with his self-published comic book Samurai Jam. This attracted the attention of US publisher Slave Labor Graphics, which published several of Watson's works ever since (e.g. Skeleton Key and Slow News Day).

Watson has also created miniseries and graphic novels for Oni Press (Breakfast After Noon, Love Fights, Little Star) and DC's new label Minx (Clubbing). Currently, Image Comics ist publishing Glister, a comic about a young girl who attracts unusual and magic occurences.

Apart from his rather personal indie works, Watson is also working as an author for mainstream comics like Buffy the Vampire Slayer or Star Wars (Dark Horse).

CG: Breakfast After Noon is your first published work in a German translation. Stefan Heitzmann, your publisher, says on his website that this is your best work. Do you agree?

AW: Uuuuhm… no. I think the latest work is maybe the best work, but Breakfast After Noon ist the most classicly structured, the way the story is put together. So I can see it's more satisfying to read, whereas the Little Star book I just finished wasn't structured as carefully. The ending was much more open. The characters don't necessarily learn anything, there's not a lesson in the end, whereas in Breakfast After Noon there's kind of a moral subtext.

CG: But it's a good point to start reading your work, isn't it?

Yeah, I think so. It's probably the best way to start, and hopefully it's not downhill from there (laughter).

CG: If you could choose a follow-up book in Germany, which one would you choose?

AW: Maybe something like Slow News Day, because again it's more traditionally structured, more like a three-act movie, and it has a happy ending. It's in a very accessible genre, it's kind of a romantic comedy with office stuff. I'm not sure how it really translates to Germany, with the local newspaper and how much that would make sense. But then, thinking about Little Star, I know that the way the gender divides in Germany is a bit different. Moms generally stay home and dads generally go to work. So I'm not sure how accessible that would be to German culture. But probably, if German people are used to watching Hollywood movies and enjoy them, then something like Slow News Day would be a good next step.

[Editor's note: Meanwhile, Little Star has been chosen to be Andi Watson's second work to be translated into German]

CG: Speaking of happy endings: Breakfast After Noon has a kind of happy ending, not a real Hollywood ending, but still not a sad ending. When I was reading it, I wondered if you considered giving it no happy ending, but a sadder one instead?

CG: Speaking of happy endings: Breakfast After Noon has a kind of happy ending, not a real Hollywood ending, but still not a sad ending. When I was reading it, I wondered if you considered giving it no happy ending, but a sadder one instead?

AW: I think the point of this story was that Rob goes down and then he has to pick himself back up again. I mean, if he goes down and then he goes down and that's the end, I don't think there's much emotional payoff for the reader. But I always had a kind of an unravelling ending, because you don't necessarily know how stable their relationship is in the end. It's kind of when the child comes along, it really galvanizes Rob and he kind of grows up. I wasn't thinking: „If I put a sad ending to it, it would be a less successful book“, but that was just the way I built the characters: Rob does not necessarily learn a lesson, but he changes over the course of the book. If he was kind of selfish, and then he was more selfish, then there's no real story, there's no drama, no turnaround. Whereas when he's a selfish prick for a while and then he sees the consequences of his ways, it's a more interesting book to read, I think.

CG: You live in Great Britain but you do most of your work for American publishers. Is there a notable comics scene in England, except for 2000 A.D., which is the only thing I know about?

AW: Yeah, that's really pretty much it. There's always a kind of small press, fanzine, underground thing happening. But if you want to make money drawing or writing comics, you have to go the the U.S. and work for DC or Marvel and generally do superheroes. That's the way most people do it, but the way graphic novels are taking off, things are changing. Publishers like Walker Books are beginning to produce comic book adaptations of children's books like Stormbreaker. I think they see there's a growth market and maybe things will take off in England. I hope that publishers will invest in English creators. Lots of companies like Jonathan Cape just republish American authors. I don't understand that. You want to grow your own homegrown talent and people who talk about your own culture. I understand that something like Palestine by Joe Sacco is a great book but I just don't see why you necessarily need to buy it from an English publisher. If people want it, they can get hold of it. I wish they put more money into their own grounds and really grow a comic culture within the U.K.

CG: Are there any problems for you working for American publishers when everything has to go trans-atlantic? Do you miss personal contact, or do you actually have personal contact to your publishers?

AW: Before I had a child, I used to go over to the American conventions every year. I noticed that it really pays off to do that. Because when you skip that for a few years, you kind of slip off the radar, you don't exist anymore. I mean the work itself is fine, it's all e-mail and FTP, everything is digital anyway nowadays. You just download and upload stuff, so there's no problem. But yeah, I think that putting a face, an actual physical presence at a convention, makes much more of an impact than just sending e-mails and stuff. You gotta keep going over. Even if you're losing money on the short term, it's kind of a long-term investment. „Hey, I'm still alive, I'm still here, I'm still working“ rather than just disappearing. Because the Americans don't come over to the UK conventions. It's a very small scene in the UK, so it doesn't make financial sense for them to do so. You have to go to them really.

AW: Before I had a child, I used to go over to the American conventions every year. I noticed that it really pays off to do that. Because when you skip that for a few years, you kind of slip off the radar, you don't exist anymore. I mean the work itself is fine, it's all e-mail and FTP, everything is digital anyway nowadays. You just download and upload stuff, so there's no problem. But yeah, I think that putting a face, an actual physical presence at a convention, makes much more of an impact than just sending e-mails and stuff. You gotta keep going over. Even if you're losing money on the short term, it's kind of a long-term investment. „Hey, I'm still alive, I'm still here, I'm still working“ rather than just disappearing. Because the Americans don't come over to the UK conventions. It's a very small scene in the UK, so it doesn't make financial sense for them to do so. You have to go to them really.

CG: Could you tell us a little bit about the differences between working on licensed properties – you worked on Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Star Wars comics – and actual creator-owned work? I think there must be huge differences…

AW: I'm my own boss with my own work to some extent. I mean there's still deadlines and stuff that you have to meet. Working on licensed things like Buffy or Namor which I did for Marvel, you're working for a boss who has some expectations of what the work is going to be. You have to do what you're told, basically. You don't necessarily play to your strenghts — like, Namor was kind of an action-adventure comic for boys, and yet they wanted kind of a romantic story to it, but the two just don't meet.

It's hard and it's not very rewarding creatively, but you get paid for it. That's basically the reason to do it. The harsh truth is that the only way to really make a living is to write a book monthly, and the rest of the time you just have to balance your own work with commercial work.

CG: I read a quote by director Steven Soderbergh, who said something like: 'I do one for them [the major studios], and then I'll do one for me.' Can you share this attitude?

CG: I read a quote by director Steven Soderbergh, who said something like: 'I do one for them [the major studios], and then I'll do one for me.' Can you share this attitude?

AW: Yeah, I can. I mean, I'd rather do 'one for me' all the time, but it's not always possible. I think it's just a matter of keeping your own ball rolling and making sure that you keep going back to your own work, working on your own ideas. It's very easy to be seduced by work for hire, it's reasonably comfortable and you get paid regularly and all this kind of stuff. It's easy to fall into that and just hack out work for other people that has no meaning to you and is not really of any worth. Anyway, it just fills a slot in the publishing schedules…

So it's a constant battle, trying to make a living and express yourself in a way that's fulfilling.

CG: But this balance does work for you…

AW: Generally, yeah. I mean, again, you have to keep going to the conventions and meet people face-to-face. And you have to at least appear enthusiastic about working on Buffy the Vampire Slayer even if you're not, you kind of got to keep yourself open to do that kind of thing. I mean, I'd rather write novels or something, but there's no money in that either, so basically I have to keep going back to Marvel and DC and begging for work. It's not fun, but it has to be done.

CG: On my way to Frankfurt, I read your graphic novel Geisha. In the subplot, there's a lot of „art versus commerce“ going on. I suppose this is a quite important subject for you.

AW: Yeah, I find it a really interesting subject. There's another work I did called Love Fights, which hasn't been translated so far, except into Spanish, where the characters live in a world where superheroes are real and have copyrighted likenesses. You know, this kind of world where art and commerce clash which is really interesting. I guess that comes up all the time. I think there's lots of drama there. Even in Slow News Day, it's the same kind of thing: working on a small newspaper with a small audience versus doing a sitcom with a huge audience on TV. It's always a great source of conflict for characters trying to be true to themselves. It becomes more and more relevant, I think, because the way the media becomes globalized…

AW: Yeah, I find it a really interesting subject. There's another work I did called Love Fights, which hasn't been translated so far, except into Spanish, where the characters live in a world where superheroes are real and have copyrighted likenesses. You know, this kind of world where art and commerce clash which is really interesting. I guess that comes up all the time. I think there's lots of drama there. Even in Slow News Day, it's the same kind of thing: working on a small newspaper with a small audience versus doing a sitcom with a huge audience on TV. It's always a great source of conflict for characters trying to be true to themselves. It becomes more and more relevant, I think, because the way the media becomes globalized…

Something like Friends sold in multiple markets around the world. But there's a growing pressure to not do anything too specific or too local, anything that could alienate viewers around the world. I think it's an interesting subject, a subject I touch in Breakfast After Noon: the main character, Rob, works for a British ceramics company and then he buys his cups and saucers from Ikea. People don't really put these things together in their head but what they buy has an impact on the world around them and effectively Rob helps to lose his job by doing that.

CG: Apart from writing and drawing your own books you also write for other artists, like Paris (with Simon Gane, SLG Publishing). What's the difference between writing for yourself and writing for somebody else?

CG: Apart from writing and drawing your own books you also write for other artists, like Paris (with Simon Gane, SLG Publishing). What's the difference between writing for yourself and writing for somebody else?

AW: Writing for other artists is very satisfying when you're playing to their strengths. Something like Paris has very few panels per page and more attention to architectural details or girls kissing. It wasn't necessarily something I was interested in, but Simon really wanted to do that kind of stuff, so he gave me a shopping list of things he wanted to draw and I took those and incorporated them into the story. And yeah, it's fantastic when the pages come back from Simon with these beautiful Paris scenes, that's just a great experience. This is the first time I really got that buzz, because before that I did just work for hire as a writer and not something I was that attached to.

CG: Have you ever drawn after somebody else's script?

AW: Yeah, just small things, nothing big. Like this DC book called Bizarro which is a big collection of short stories, and I've drawn some stories by Evan Dorkin and some other people. It's interesting, 'cause writers make you draw things you wouldn't normally draw. If a writer made me draw comic strips with a traffic jam, it would be a real challenge 'cause I hate drawing cars and I'm not very good at it. So, it's good to be pushed into regions you wouldn't normally dare to go. But with comics, the pacing and the way the page is layed out are so important that it's hard to feel connected, unless it's two people who are really of the same mind and really interested in the same things. That's the case with Paris, Simon and I were really into the same stuff: art and Ingres and classical paintings and all this kind of stuff. We really agreed.

So in this case it worked, but I'm not sure how funny it would be to draw a graphic novel about a traffic jam. You know, just cars and cars… It can be interesting, but I prefer to work on my own stuff whenever I can.

CG: Speaking about drawing: almost all of your books are in black and white. Maybe for financial reasons, but maybe also for artistic reason. What are your views on colour versus black-and-white?

AW: Black and white is much more direct and it takes less time. And you can get the same effects from black and white if you have experience of working in black and white. And of course, there's the financial aspect. In colour, you can change the emotional tone of a panel by different colours, but then you have to balance all the panels on the page. It's a lot of more work, there's a lot more involved.

AW: Black and white is much more direct and it takes less time. And you can get the same effects from black and white if you have experience of working in black and white. And of course, there's the financial aspect. In colour, you can change the emotional tone of a panel by different colours, but then you have to balance all the panels on the page. It's a lot of more work, there's a lot more involved.

So, ideally, if I was gonna do something in colour, I'd like to work with a really good colourist who I'm on the same wavelength with. Something like Hellboy, which is really beautifully coloured. The colouring is a storytelling element, the way it's put together. Mike Mignola obviously works in black and white, but he has the colour all in his head, how it's gonna play out on the page. I mean, I admire the way that works but I also am somehow intimidated by how difficult it is.

I'm used to work in black and white, and it's just a whole lotta more things to juggle, putting the page together. But yeah, it's great when you can get different emotional effects but it's another couple of hours on the table, in front of your computer. But I think you can get the same effects with black and white, and it just doesn't take as long, which is always good.

CG: Ironically, speaking of Hellboy, the German publisher of Hellboy does it in black and white, because he says for him it looks better in black and white and Mignola made it in black and white. And everybody, well not everybody but a lot of people seem to be very enthusiastic about it, even Mignola himself and Dark Horse gave him feedback that it looks great in black and white. I think it works in both ways.

AW: Yeah, definitely. I've seen his work serialized in Dark Horse Presents in black and white and it's fantastic. He just knows how to balance a panel and do the solid blacks versus the areas of white. He's just brilliant at that. And yeah, I'd buy both.

CG: You can check it out, their booth is just across the floor of Modern Tales's booth.

AW: Oh, great! I'm interested in getting a copy of that.

CG: My last question is about Manga. Manga is one of your influences as well, especially in your early work. Here in Germany, we have a very divided market. There's the manga crowd and there are the other guys who like western comics and while there are a few publishers who do both, most of the readers do just read either manga or western stuff. Everything is very divided, and I think in the U.S. and in the U.K. it's similar. I think it's a tragedy, because everybody can tell good stories in sequential art. What do you think, how could we change that?

AW: I think it will change over time. It's not gonna happen immediately, but the kids who are into manga now are gonna want to draw their own comics. Some of them will just want to slavishly follow manga styles but I think many of them will start incorporating different elements, you know, western comics and illustration… And, over time, I hope it will not be as divided and the two will kind of merge together. That's what happened in France a bit, there's a movement where they specifically take both elements. But to me, it's all visual storytelling. Comics is really a universal language.

I can understand younger readers being kind of very hardcore. It's like music, you know: you listen to heavy metal and you don't listen to anything else, or you just listen to punk rock. I think when people get older, they'll be hopefully less uptight about labels and belonging to something. But anyway, to me there's something to take from bandes desinees and from manga and from superhero comics. Movies and novels and fine arts and painting, it's all there to take, it's all free to use and be inspired by.

I can understand younger readers being kind of very hardcore. It's like music, you know: you listen to heavy metal and you don't listen to anything else, or you just listen to punk rock. I think when people get older, they'll be hopefully less uptight about labels and belonging to something. But anyway, to me there's something to take from bandes desinees and from manga and from superhero comics. Movies and novels and fine arts and painting, it's all there to take, it's all free to use and be inspired by.

CG: It shows off in your work…

AW: Thanks! Yeah, I mean, you just gotta keep your eyes open. Otherwise, you'll end up drawing in one way forever and you'll lose the energy and the enthusiasm for it. You just gotta be constantly open to new things, otherwise you just grow old and boring (laughter).

andiwatson.biz: Andi's official website

Andi Watson at Oni Press : Information and previews

Andi Watson at SLG Publishing: Blog entries about Andi's comics

Andi Watson at Modern Tales: Information and previews (in German)

Image sources: Andi Watson, slgcomic.com, onipress.com, darkhorse.com, modern-tales.de. Photographs: Thomas Kögel