Born in New Jersey in 1950, Howard Chaykin likes to draw good-looking action heroes, preferably of Jewish descent, with a soft spot for guns, women and snappy one-liners – and he’s been at it for more than 30 years, at this juncture. Chaykin’s art for Marvel’s Star Wars comics made him popular, works like The Shadow, Black Kiss or Power & Glory caused quite a stir in their time, and his caustic sci-fi satire American Flagg! made Chaykin one of the most influential American comics creators.

At 61, Chaykin remains a prolific storyteller. His recent comics projects include short stories starring the Spirit and the Justice Society for DC Comics, the miniseries Avengers 1959 at Marvel and his own comic strip in the Eisner Award-winning anthology series Dark Horse Presents. As of July 2012, Chaykin is at work on Black Kiss 2, a project with writer Matt Fraction titled Satellite Sam, as well as a new miniseries starring sci-fi hero Buck Rogers.

At Comic-Salon Erlangen 2010, Marc-Oliver Frisch sat down with a good-humored Howard Chaykin to talk about art, ego and hip-hop – and some grown-up stuff, as well.

Interview: Marc-Oliver Frisch. Photograph: Christopher Bünte

[LESEN SIE DAS INTERVIEW AUF DEUTSCH.]

MARC-OLIVER FRISCH: I read your conversation with Ho Che Anderson in the Comics Journal, where you call yourself a journeyman, but you also say you want to be a “brand” that the publishers and the audience can rely on. That was very interesting to me, because people don’t tend to take the term “journeyman” as a compliment.

HOWARD CHAYKIN: Really? Well, I was thinking of… Do you know jazz at all?

FRISCH: Not really, no.

CHAYKIN: With a hat like that you should.

FRISCH: I know.

CHAYKIN: One of the great white jazz musicians of the 1950s through the 1970s was a guy named Gerry Mulligan, who was known as the great white mainstream, and also the great journeyman player. And I think in the context in which I used this phrase, it meant that I was not a guy who was particularly special at this, or that, or the other thing, but that, when called upon, I can do anything. I can do war stories, westerns, crime, romance, which is much more what… You see, if you ask me a simple question, you get a long answer. It’s more like what the generation before mine did, because those men… Let’s face it, the guys who were the Bullpen, Stan’s first artists, after Jack, all came from the DC romance department. You know, John Romita, Don Heck, all these guys who’d been languishing in romance comics. But the truth is, I always was raised to believe that I should be prepared to do any genre that comes along. Which does in no way obviate the fact that, if I do a western story, a science-fiction story, a crime story, a superhero story, that there’ll be a signature imprint of who I am in that material, that you know it is a Howard Chaykin story first, branded upon that character.

“I recognize that

I’ll have two weeks of good ink

when I die, and then

I’ll be forgotten.”

I don’t think of “journeyman” as a disparaging remark. I think it states that I’m a man among men and a worker among workers. I recognize that I’ll have two weeks when I die, two weeks of good ink, and then I’ll be forgotten. And I’m okay with that. I mean, I have an ego. Don’t get me wrong, I do have an ego. But I’m also reasonably comfortable with my own insignificance. It’s just not that important. I mean, I love the work I do, but I like doing the work more than I love the work. Does that make sense? It’s the process that matters to me.

FRISCH: It’s my impression that you’ve found a way to express your ego, and to express yourself, that doesn’t clash with reality.

CHAYKIN: I have a pretty reasonable sense… I’m right-sized. I had a long conversation last week with a very good friend of mine who I don’t see enough, a writer whose first novel is just brilliant, was well-received, and whose second novel was ignored, though it’s a wonderful book, a terrific book. And we talked about failure. We talked about being comfortable… about getting past the bitterness and the anger and recognizing the fact that you can’t control what it’s gonna be next. I’m very proud of the work that I’ve done over the last 30 years, some of which has been met with indifference, and I have no idea why this was met with indifference and this wasn’t. It is such a crapshoot and such a luck of the draw. And it’s true of all… it’s true in television and true of the movies… Look, Crazy Heart, the Jeff Bridges picture, it was almost a release to video. It was almost never released theatrically, because the studio thought it was just a piece of shit, you know. And then it’s this huge massive hit, it’s The Wrestler with guitars. It’s not a great movie. It’s only a good movie. But it’s a very good movie if it’s a very successful movie. Gil Kane once said, “Is it popular because it’s good, or is it good because it’s popular?” There you go.

FRISCH: It seems you’ve achieved a pretty good balance in your career, in terms of where you are in the industry, what you want to do and how to approach it.

CHAYKIN: I think that’s true.

FRISCH: Many people in comics don’t have that.

CHAYKIN: How do you mean?

FRISCH: You’ve got a lot of creators who don’t get to make a living doing the things they really want to, whether it’s company-owned or creator-owned work.

CHAYKIN: I mean, one of the reasons that I mostly do work for hire right now is that I’d like to make a living, you know. I’m older than a lot of my colleagues. When I came into the comic-book business, I was the youngest of my crew. I was the youngest by a number of years. But I’m now among the oldest, and I… I have a lifestyle to support. You know, I am lucky enough to live where I live, to be in the financial position that I’m in. But I still enjoy the process, for example, of being able to come to a comic-book convention in Europe. I’m a guest of the show, I bring my wife… I need to make a living. I am going through some real hunger right now to do something other than the work-for-hire stuff that I’m doing. I’ve been craving that. I’ve got two projects that I would very much like to be doing.

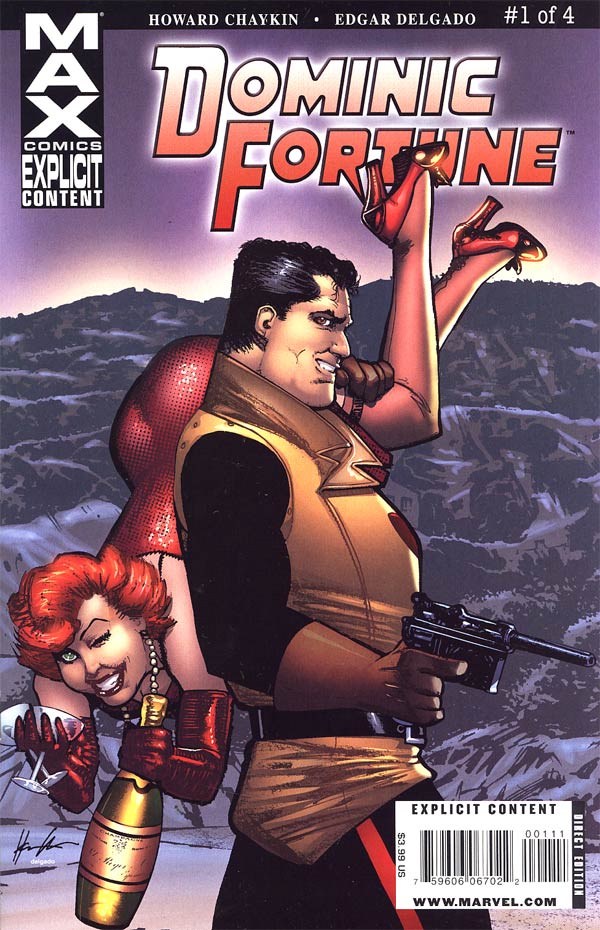

FRISCH: You’ve been doing a lot of work for Marvel lately, like Blade or Wolverine or Phantom Eagle. The one I’m wondering about, though, is the new miniseries with your creation Dominic Fortune that just came out.

FRISCH: You’ve been doing a lot of work for Marvel lately, like Blade or Wolverine or Phantom Eagle. The one I’m wondering about, though, is the new miniseries with your creation Dominic Fortune that just came out.

CHAYKIN: It’s pretty funny. I had a great time doing it. This was also the first time I saw anybody else’s Dominic Fortune stuff. I’ve never seen anything else that anyone else has ever done with Dominic Fortune at Marvel. This is a character I love writing and love drawing, and this was an opportunity to do stories and concepts I’ve had in my playbook for years, that I’ve always wanted to do.

FRISCH: How did it work out for you, creatively? Would you say this is more of a Marvel comic, or more of a Howard Chaykin comic?

CHAYKIN: I had very little editorial… They let me do pretty much what I wanted. I mean, the changes I had to make were all oddly graphic. They were in the covers. I couldn’t use the Olympics symbol, it was copyrighted, and I couldn’t use a swastika on a cover… because of you guys. [Meaning Germany, where you can basically get into trouble for using Nazi symbols in non-educational contexts, which has led U.S. publishers to modify artwork accordingly. –ed.] But other than that, not really. I mean, I was pretty much given free reign. You know, because the way the book started was, Axel [Marvel editor Axel Alonso –ed.] called me up and said, “You know what I’d really love to see?” and I said, “What’s that?” and he said, “How about a Dominic Fortune Max series?” and I said, “Fuckin’ A! Yeah!” [Max is Marvel’s “mature readers” imprint. –ed.] And I basically threw everything at it, assuming editorial would have me change stuff, but [snaps fingers] I had very little editorial jostling. And I was gratified and pleased, very happy about that.

FRISCH: You’ve done a lot of mainstream work, although your style doesn’t necessarily play well with some mainstream sensibilities.

CHAYKIN: Such as…?

FRISCH: People tend to be touchy about the sexual stuff and violence that’s in there, for instance, and when it does comes up, nobody wants to admit it’s there.

CHAYKIN: Is it there? In what context was it? Give me an example.

FRISCH: Frank Miller’s Daredevil comes to mind – the scene where Bullseye stabs Elektra is supposed to be a rape metaphor.

CHAYKIN: I thought he was just killing her. Who said that?

FRISCH: Miller did.

CHAYKIN: He’s a drunken idiot. [Pause] You needn’t put that in the interview… Did he really…? When did he say this?

FRISCH: There’s a documentary that came with the Daredevil movie DVD that has an interview with Miller. That’s where he says it. [The passage in question, from the film The Men Without Fear: Creating Daredevil, is on Youtube. It starts at about 9:15. –ed.]

CHAYKIN: Okay. So that’s what he meant? I never got that. I mean, I’ve only seen the panel, I’ve never read the book.

FRISCH: It seems like a good example of a lot of the stuff that’s appearing in superhero comics right now.

CHAYKIN: Did you think that was metaphoric for rape?

FRISCH: [Pause] It didn’t occur to me when I read it. But I read it a long time ago, so I don’t know.

CHAYKIN: My feeling is, if it’s rape it’s rape, and if it’s murder it’s murder, and you don’t need a metaphor to cover your ass. That’s just in my opinion.

FRISCH: That’s what I was trying to get at, because your work is a lot more explicit than most mainstream stuff. You don’t mince words.

CHAYKIN: I don’t feel the need to. I mean, my feeling is, I’ll always provide an editor the opportunity to change stuff, I mean… Even on adult creator-owned material, I’ve had to backpedal on material in places, mostly involving racist remarks, or sexist remarks, or racially insensitive remarks which I feel are justified by the characters speaking, but the editor… I’m choosing my words very carefully… but the editor feels that – and, frankly, rightfully so – that most readers… I shouldn’t say “most” readers… some readers aren’t canny enough to separate the character from the writer.

“Occasionally,

the tenderness, sensitivity

and pussiness

of many comic-book readers

has scared me.”

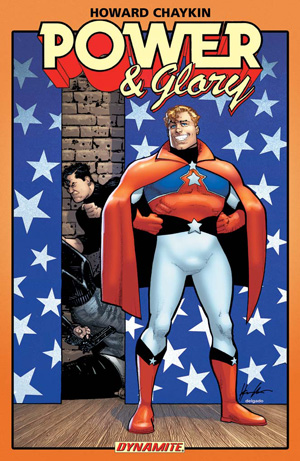

For example, when I did Power & Glory, I had the President of the United States tell an incredibly offensive joke, which I had heard from a friend of mine, and I was excoriated for this. And the fact is, the function of the telling of the joke was to confirm and convey the character of the president. And I was trying to use the joke to explain the fact that the character is a shitbird. And I find it astonishing that the… I do find occasionally the tenderness, sensitivity and pussiness of many comic-book readers has scared me. It’s like, you know, be a man. Except, I mean, it took me a while. I mean, I was a prudish kind of guy as a younger man, but I gave up my prudishness, you know.

For example, when I did Power & Glory, I had the President of the United States tell an incredibly offensive joke, which I had heard from a friend of mine, and I was excoriated for this. And the fact is, the function of the telling of the joke was to confirm and convey the character of the president. And I was trying to use the joke to explain the fact that the character is a shitbird. And I find it astonishing that the… I do find occasionally the tenderness, sensitivity and pussiness of many comic-book readers has scared me. It’s like, you know, be a man. Except, I mean, it took me a while. I mean, I was a prudish kind of guy as a younger man, but I gave up my prudishness, you know.

And I accept the fact that with some stuff, my taste is irrelevant. I mean, let’s take hip-hop. Hip-hop was designed to piss me off. Every generation’s music is designed to piss their parents off. It’s their job! You know, it’s like… I went from being a folky to a jazz fan, and a little bit of rock’n’roll, but not as much. That music was there to piss my parents off, and hip-hop is music to annoy my generation, and that applies to all social behaviors and tastes.

And if you don’t like this material, if it offends you, okay, don’t read it, ignore it, acknowledge your feelings about it. But acknowledge you further the fact that it has a right to exist. And that… Look, I’m a great believer in a plural society, and I oppose censorship of all kinds. I mean, there’s stuff that pisses me off, there’s stuff that embarrasses me, but I’ve no desire to stop its existence, you know. I mean… I’m a great believer in a group conscience. If something pisses me off, I tell my colleagues, and if they don’t agree with me, I move on. If they agree with me, we’re ganging up on it and fuck with these people. But if I’m alone in my feelings: okay, whatever. You know, there’s a tremendous desire to impose one’s tastes on others, and I really don’t give a shit whether you agree or disagree with me. Just simply leave me alone to my work and let me do what I’m doing.

FRISCH: Steve Gerber in the late 1970s said that he was very frustrated that people took everything he had his characters say literally.

CHAYKIN: Exactly! That’s exactly right.

FRISCH: You’ve been around as long as Gerber…

CHAYKIN: … and I’m not dead.

FRISCH: … and you’re still alive… so, do you think it’s gotten better? Do you think there’s been any change at all?

CHAYKIN: I think it’s gotten worse. Because I think there’s… I think, to confound things… I don’t know what it’s like in German. I can’t speak for Germany. But I can certainly speak for the United States in general and for California in particular, and the reading of material is more and more seen through the scrim of personal affront.

You know, it’s like… When I was in my 20s, I met Archie Goodwin, and Archie was instrumental in wooing me and weening me away from being a science-fiction reader to reading crime fiction for entertainment, and he ruined science fiction for me. I just lost my interest in science fiction. And so I went and I consciously explored all the various divisions of crime fiction, you know, from Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, including the British stuff, and I read a lot of Dorothy Sayers’ writing. And Dorothy Sayers was a perfect example of a particularly British anti-Semitic sensibility that existed in the first half of the 20th century. And it took me… There was an effort on my part to get past that to enjoy the material. And I did.

“The reading

of material is more and more

seen through the scrim

of personal affront.”

I was 16 years old, and my girlfriend then took me to see Herbert von Karajan playing at Carnegie Hall. And my mother, who was a Popular Front Democrat, said, “You know Von Karajan was Hitler’s favorite conductor?”, and I said, “Okay, you know. But I’m gonna go anyway, because my girlfriend will fuck me if I go.” And that was that.

And I recognize that there is a separation of arts… that you can still… I mean, look, Ludwig Hohlwein… Ludwig Hohlwein, he was a great advertising artist in the 1910s and ‘20s in Germany, and he became a great poster artist for the Nazis… fantastic stuff, the greatest. And he… fuckin’ A, it was dynamite… And, you know, it’s appalling… it’s imagery in the service of the appalling, but it’s pretty astonishing stuff. You know, it’s the same way with Leni Riefenstahl – it is what it is. Though Riefenstahl was crazy… and interesting… So I’m willing to look at shit and accept the fact that this is the work as it is – there are elements of it that are appalling and there are elements of it that are offensive, but leave me the fuck alone, and I’ll leave you the fuck alone. That’s a long answer to a short question.

FRISCH: Denny O’Neil said in a recent interview that U.S. comics creators are generally better off now than they were back in the day. Do you agree?

CHAYKIN: Oh, absolutely. Unequivocally, yes. I made no money. I was treated like shit. And there was no respect. The difference really is that today, thanks to the guys who did Image, this puffed-up version of themselves, they still created an atmosphere and sensibility that made it possible for us to get a bigger piece of the cake.

I mean, I try not to take advantage of it. I mean, I have a very strange reputation, because in the fans, I’m regarded as an obnoxious asshole, and yet – [raised eyebrows] oh no, they say it, trust me. Believe me, I have no illusions or confusions about who I am – while, in the context of the profession, I’m regarded as a go-to guy that can be depended on all the time, and it’s a very different relationship. And I’m more interested in being well-received by my colleagues and my employers – my clients – than I am that I give a shit about the fans. I mean, I was a fan. I have a picture of myself at 17. I weighed 265 pounds, and I was that kid. I was those guys. But I’ve learned a certain distance.

I said once that for comic-book readers, it’s every Wednesday at the book store, for me it’s every morning on my desk. And that makes a difference in the relationship. But I love the process, enormously. I’m very… I am so grateful.

FRISCH: You’ve said that the audience for comics is not so much the actual readers anymore, but the comics-store owners.

CHAYKIN: Yeah, absolutely. They’re the ones who dictate what sells and what doesn’t sell. I don’t know if that’s true in Europe, but it’s certainly true in the States. And the same is true in television and in movies.

“There are commercial

comic-book successes that are

utterly inexplicable to me. You

know, things that are

just like, this is just shit.

This is embarrassing horseshit.

And yet people eat it up

with a spoon.”

Who you’re selling to is the assistents to the boss, because they’re the ones who are the gatekeepers. The retailers in the States are the gatekeepers. They’re the ones who say, “Read this, read this, don’t read this, this is disgusting, this guy hates me, don’t read this,” you know, that kind of stuff, so it is the retailer who dictates what the audience responds to. I mean, within reason, of course, there are frenzies, but there are also commercial comic-book successes that are utterly inexplicable to me. You know, things that are just like, this is just shit. This is embarrassing horseshit. And yet people eat it up with a spoon. And I won’t say what they are.

FRISCH: You’ve said…

CHAYKIN: [silly] I will not name names.

FRISCH: So, you’ve said…

CHAYKIN: [sillier] No! Don’t even… You with your fucking hat!

FRISCH: Well.

CHAYKIN: [doing a singing, swinging, full-tilt Frank Sinatra impression] Come fly with me, da da da da da…

FRISCH: Right, that’s me. So, you’ve said you like Criminal.

CHAYKIN: I loved it, it’s a great book.

FRISCH: Ed Brubaker seems to be a guy who’s found a particularly good balance between creator-owned stuff and work for hire.

CHAYKIN: It’s easier to do for a writer than for an artist. Because it takes a lot less time to write a page than it takes to draw them.

FRISCH: Could you see this as a model for yourself?

CHAYKIN: Not really… not really. If I were to create… There are two creator-owned projects I really want to do. But that would mean not doing other stuff. That would mean taking money out of my line of credit. But right now… I mean, it’s an economic decision. Right now I’m carrying more debt than I want to. I mean, this is grown-up stuff, this is not comic-book stuff. In the grown-up world, I own a house, I have a line of credit against the house – I own the house all right, no mortgage – but I still owe a lot of money to this account, and I’d rather not be taking more money out of it to publish myself. And that’s what I’d have to do for a creator-owned project, because the kind of stuff I do, I’m better off publishing myself. I could distribute it through Image, but, you know. I’m gonna be doing a book for a small British press that’s run by a very good friend of mine. I have two crime books that I’d want to do, that I know would at least find something of an audience, that wouldn’t generate enough cash for a major publisher but would be fine for me. But I’d have to finance it. It’s like I say, it’s grown-up stuff. It’s not comic books, it’s the real world.

Images: © Howard Chaykin/Marvel Comics/Dynamite Entertainment