“Don’t worry,” Reprodukt’s press contact Jutta Harms told us, calmly, “he’s very reliable. He’ll be here on time.” And, sure enough, just before the agreed time of the interview, James Sturm showed up at the Künstlerhaus am Lenbachplatz, the location of this year’s Munich Comics Festival, back from exploring the city on his own.

The American cartoonist and Eisner Award winner had begun his first visit to Germany with a stop in Berlin a few days before. The occasion was Sturm’s inaugural German release, Markttag, a translated edition of his 2010 book Market Day. Released by Reprodukt, whose head honcho Dirk Rehm was just given the ICOM Independent Special Award for Remarkable Accomplishments, Markttag is in the company of high-quality bookshelf editions of the works of Arne Bellstorf, Joann Sfar and Craig Thompson, among others.

But though we were only going to have half an hour to talk before a scheduled signing, there were no worries that Sturm might be late. I had seen his lecture and subsequent panel talk with Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung editor Andreas Platthaus at the Amerika Haus the night before, and the man’s appearance—eyes smart and alert, his face shaved clean, the gray on his head trimmed to a neat stubble—radiated an air of solidity. Sturm’s voice is soft but firm, and while he is the kind of speaker who tends to intone statements as if they were questions, it’s pretty clear that he doesn’t do it out of insecurity, but because he is, quite simply, aware that he doesn’t have all the answers.

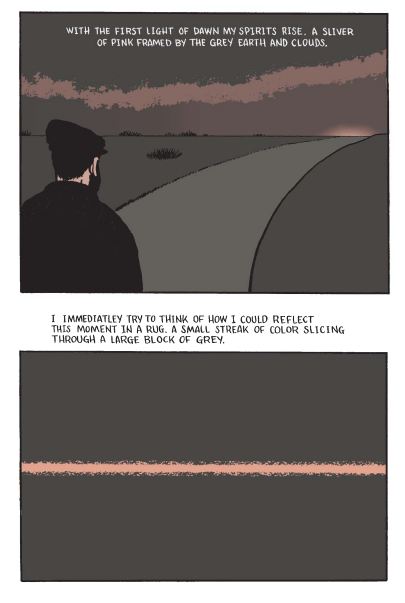

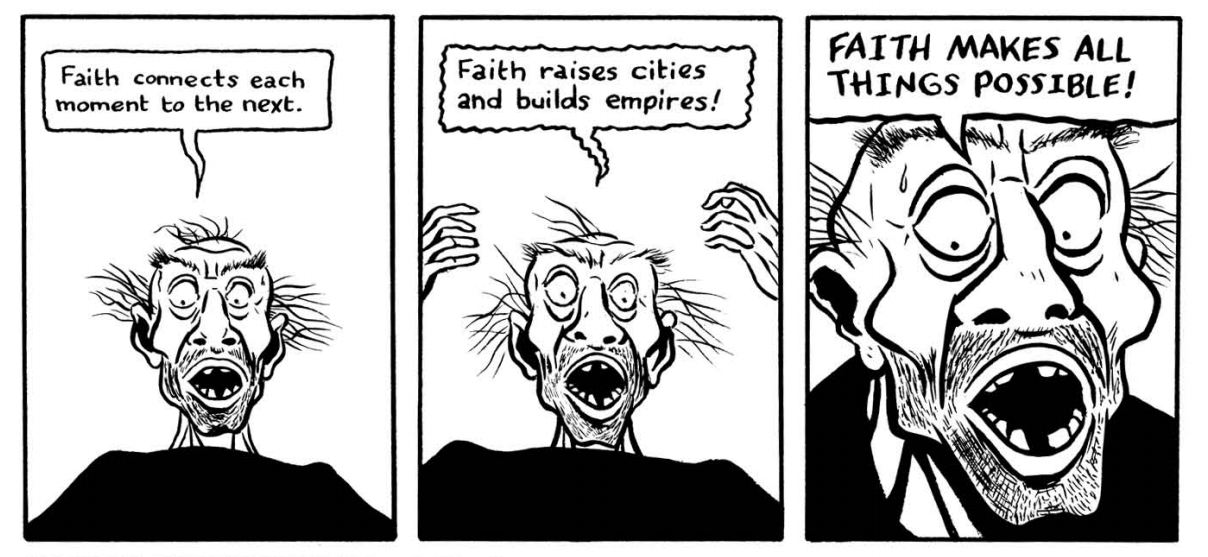

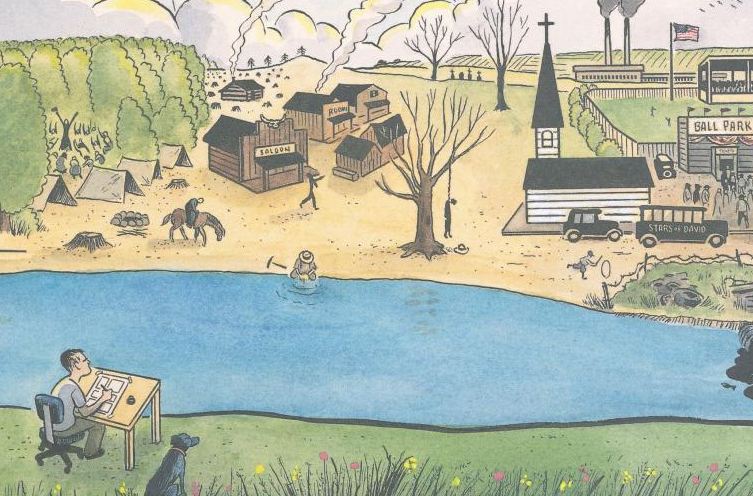

In short, even if you are not familiar with Sturm or his work, it’s obvious he’s a well-adjusted individual who has found a way to reconcile his muse with the necessities of life. And if you are, seeing Sturm in the flesh will only confirm what you probably suspected about a 45-year-old husband, father and teacher who in 2004 founded his own school, the renowned Center for Cartoon Studies in Hartford, Vermont, and whose works are historically grounded explorations of themes such as faith (The Revival), the gold rush (Hundreds of Feet Below Daylight) and Jewish identity (The Golem’s Mighty Swing; all three of which collected in James Sturm’s America: God, Gold and Golems) or, like Market Day, deal with the struggle of finding a middleground between, duh, making art and making a living.

Somewhat appropriately, perhaps, the location we secured for our talk ended up being not hundreds of feet below daylight, but quite a few all the same, down in a remote corner in the labyrinthine basement of the Künstlerhaus, a building opened in the year 1900, at the far end of a dark historic bowling alley mildly reminiscent of the one from There Will Be Blood. After repeatedly reassuring a concerned Mr. Sturm that murder was not on our minds, he was game for a quick photo session, and then we finally sat down to talk.

Interview: Marc-Oliver Frisch; photographs: Björn Wederhake

(LESEN SIE DIESEN ARTIKEL AUF DEUTSCH.)

COMICGATE: Let’s start with a really simple question: If one of your students walked up to you and asked you, “Why make art?”, what would you tell them?

JAMES STURM: (laughs) I’d be surprised if one of my students did ask that question because, by the time you get to be one of my students, it’s a moot point, because you know that you are compelled to do it. And the answer to that is a mystery beyond mysteries. It’s something that emerges… that’s contained in your very deepest place, and you have to do this thing. And these are the type of students that we try to get. In that field it’s an imperative to make art. I would not even offer an explanation. I mean… You know, there’s all kinds of things you could say that sound lofty and significant, but at the end of the day, for an individual, “Why make art?” Because you have to.

COMICGATE: I’m asking because, in Market Day, the protagonist, Mendleman, is weaving rugs, and his friend makes chairs. But those are items of daily use, and even for them it’s a challenge to juggle art and commerce. So, I imagine with comics it’s even harder to justify, because there is no tangible daily benefit to “using” them.

JAMES STURM: I think the discipline of making art, for me… It helps me understand the world. It’s my way of arranging all the images, all the impressions that I get, and trying to find some type of through-line, some type of theme, so when I start getting lost in this world, I can start drawing. And that helps me create some type of schematic, where I can get grounded again. And I think, ultimately, this is the benefit for me of making art. It allows me to feel I have some type of understanding. Sometimes it allows me to feel I have some type of control, which is important. And I derive a lot of satisfaction, both from the hard work and the process of working towards something, and then, of course, from meeting a goal and creating a book that is a result from my own toil and search and aspirations.

COMICGATE: In an interview in 1999, you said that you won’t tailor your work towards attaining a massive audience.

JAMES STURM: Hmm. Yeah, I might have changed that since I said that. Well, I tailor my work… I think I’m more conscious of an audience. I think since I’ve become a father, I know that you have to tailor how you express yourself to your children. And as a teacher, you have to be more careful, because your students see you as this authority sometimes, even though you don’t feel like an authority. So you have to be a little less flippant. And, you know, I’ve created some childrens’ books and books for younger audiences. And I think, with those books, I feel like I’m still trying to create something authentic and meaningful, but I’m also aware of an audience in trying to tailor it a little bit so it’s appropriate for that group. So a book that I did for six-year-olds is gonna be very different than, you know, Market Day or Hundreds of Feet Below Daylight.

COMICGATE: Also, your students need to go out in the world and find a way to benefit from their work…

JAMES STURM: Yeah.

COMICGATE: …so I imagine that you needed to reconsider, because you probably can’t tell them that they shouldn’t compromise at any stage.

JAMES STURM: Well. “Compromise” is an interesting word. I think it’s okay to compromise, but it’s not okay to… to be compromised. I don’t know if that makes a distinction in German, but…

COMICGATE: It does.

JAMES STURM: …if you compromise yourself, then you give away some of your dignity. It’s not good. But a give-and-take is healthy, too. So I think… I did projects and worked on things as I was discovering myself as a cartoonist, and even now, where it maybe wasn’t the work that was an ultimate expression of who I was or anything, but it gave me an opportunity to work with certain people, or collaborate, or be in a position where I felt I would grow from the experience. And that was good. I mean, sometimes I don’t mind putting myself in a position if I feel I’m going to get something out of it, as well.

And with the students, with the cartooning, you know, you teach them all these skills. They learn to write, to draw, to design, all the posting their comics on the Internet in design. So, they have a lot of skills, so they might not sell a graphic novel for many years, or make a living in cartooning, but I feel that the creative skills that you develop in your ambition to be a cartoonist are commercial and marketable.

COMICGATE: You’ve been referred to as a “cartoonists’ cartoonist,” which…

JAMES STURM: Which means I don’t sell enough books (laughs). I don’t know if…

COMICGATE: No, the way I took it was that your characters and settings seem to be getting less specific—you’ve said that Market Day could be set at any time and in any place. Meanwhile, the concerns and themes are getting more specific, because now you’re tackling this artists’ dilemma—unlike in The Revival (1996), for instance, which is set at a very specific place and time and deals with this very universal concern of people looking to God for help. Would you agree that’s a direction you’re going in?

JAMES STURM: It’s hard to see it from where I am… If I feel like making art in some type of spiritual dimension or questions I see in my own work, I try to figure that out in the work. The Revival is about a very specific meeting that actually took place at a specific date. Market Day was broader, but there was a point in history that I was looking at. You know, it couldn’t have been any place. It’s obviously Eastern Europe, and it’s obviously the early 1900s. But no country is named, no town is named, it’s somewhere in this settlement of the pal… that could be anywhere, of course.

COMICGATE: In the way it’s told, the book is almost like a parable, but unlike most parables, it doesn’t have a moral—it’s left open. What’s your take on the idea of commenting on the work in the work itself? Do you consciously try to avoid it, generally?

JAMES STURM: I feel that the book is about showing this crossroads and this dilemma and… I think sometimes these big schisms are really false, because anywhere you look you can find something meaningful and fulfilling, but this person, Mendleman, yes, he comes to this crossroads, and I didn’t want to spell out his choice. I want the reader to take away what they take away. Some readers are very adamant that he should keep making his rugs no matter what, and others that he’s obligated to his family first. And the same with The Revival. I didn’t want to say that this faith restored this girl. I wanted to leave it more up in the air. And the response is good. I like that. I like literature or plays that people can enter and pull… sort of like Antigone. They showed that in occupied Paris, and the Germans leave thinking that was about the state over the individual, while the Parisian underground takes something else from it. I like work that can almost do that, to a certain extent.

COMICGATE: In one of the interviews you’ve done, you almost offer a solution to Mendleman’s dilemma. You said that he maybe just needs to accept that the true worth of art isn’t determined by the market, that it’s two different things, so…

JAMES STURM: Right, and he does not see that yet.

COMICGATE: …would you ever consider including that solution in the work itself?

JAMES STURM: No. I think I would consider doing another book that features Mendleman, many years later, and show him in his life, and by just depicting what he’s doing, you would illustrate the choices that he made and the consequences of those choices. Because I feel that, whichever choice you make, there are consequences, and I don’t think there are safe choices. I have friends from college who were very good writers, talented artists, and they gave up their work, because they had more middle-class aspirations, or upper-class aspirations. And I think they gave up a lot to get that. They thought it was a safe choice, but then you run into them and… they’re not happy, they’re restless. They’ve made some good money, but there’s something that they miss.

COMICGATE: They chose stability over fulfillment.

JAMES STURM: Right. But I don’t know how stable, because sometimes we sabotage ourselves at certain points. And now that I’m 40, I see people who were hardcore bohemians, and “Art!”, and they’re gonna keep squatting and live that way. And now they’re in their 40s, and they’re getting worried as their health starts to give and they don’t have health insurance, and… with some, you get the sense that they wish they’d maybe planned a little better, as well, because they were so hardcore the other way. So, I don’t know. It’s hard to say. I mean, it’s a very tricky thing, you know. I think, as an artist, you have to really commit fully, and I think this is one of the reasons that artists oftentimes don’t function so well in this world. Because you have to put some blinders on, and you have to be totally committed to the work, and sometimes that’s at the expense of other areas of your life.

COMICGATE: Another thing from the ‘99 interview that I could identify with is, you said you didn’t enjoy comics as much as you do novels, and that you didn’t think the problem was the medium itself, but that prose novelists were just producing material that’s more resonant and deeper. I was wondering if you still feel that’s the case.

JAMES STURM: That’s a good question. Well, it is comparing apples and oranges, but I feel like I could lose myself in a novel for a longer, more sustained time. You know, a novel takes a week, two weeks to read as you move through it, and it’s very absorbing in a way. And there are very few comics out there—very few comics—that accommodate that, that create that spell for me. You know, I find myself looking at a lot of comics, and enjoying the art, or there’s something about the gesture or the illustrations that is appealing to me. But in terms of then having that pull me in in a way that I’m as absorbed as I am when I’m reading a novel. Not many comics do that for me. There’s few cartoonists whose work hits me the same way.

COMICGATE: Why do you think that’s the case?

JAMES STURM: Well, it’s probably just my own composition, or my own constitution… I don’t know (laughs).

COMICGATE: Do you think maybe cartoonists neglect the writing aspect?

JAMES STURM: I’m hesitant to say, because I feel that, with some cartoonists, that’s not what their work is about. It’s more about gesture, and creating… transmitting a certain energy to the reader, and it’s not about narrative. And I think that’s a very valid approach to comics, you know. It’s a visually driven medium. Those types of works I appreciate, but they don’t sing to me on that deeper level all the time, like some other people may appreciate that work. And again, that’s just an individual taste thing for myself. So I don’t wanna damn those kinds of comics, because I actually like looking at them, to a certain extent. So I look at them and enjoy them, but they don’t stick with me and resonate in me as deeply or for any great length of time.

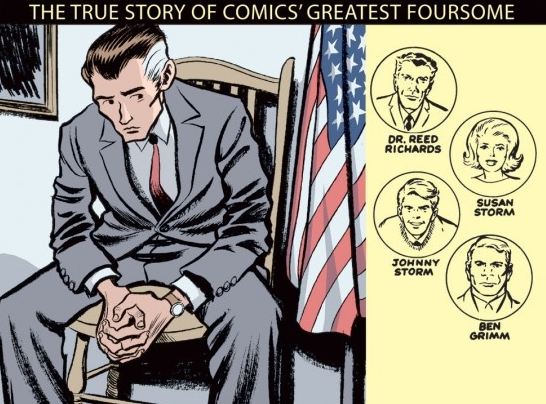

COMICGATE: Yesterday at the lecture, someone in the audience asked if you’d consider doing something like Unstable Molecules again, your Eisner-winning 2003 Marvel miniseries with the Fantastic Four, and you laid out this very intriguing project starring Thor and Hercules, who ride across America on bikes to learn humility after their fathers Odin and Zeus took away their powers…

JAMES STURM: Yeah, that was just me… blahblahblah, you know… (laughs)

COMCGATE: …with Steve Rude drawing. That sounds very appealing.

JAMES STURM: Oh, yeah. Maybe he’ll read this interview and then call me… (laughs)

COMICGATE: Right, that’s what I was hoping… (laughter) Would you consider doing something like that on your own time, because…

JAMES STURM: Well, I couldn’t do that on my own time, because this is a property that is owned by a big [company], you know…

COMICGATE: Yeah, but “Thor” and “Hercules,” they’re [not necessarily Marvel properties]…

JAMES STURM: Oh, I mean, with the Fantastic Four, the stars aligned at Marvel, and it was easy. It wasn’t a big hassle to get through the door, and I was left to make the work I wanted to make. This isn’t a project that I’d fight too hard to make happen, do you know what I mean? And so much of this is timing. I’m in the middle of many big projects. If the stars aligned in the right way, maybe, but I won’t die upset if it never happens.

COMICGATE: Unstable Molecules almost was an “all-star” indie kind of project…

JAMES STURM: Oh well…

COMICGATE: …with you writing and Craig Thompson doing covers. Did you take that package to Marvel?

JAMES STURM: I approached Craig about doing the whole book. He was finishing up Blankets at the time, and he actually drew a page of it, but I had these very specific layouts, and I think Craig felt constricted by them a little bit. And, you know, he’s really a genius, when it comes to his artwork. It’s just so expressive. And he felt it would be too constrictive for him. He did a few pages, and I didn’t want to be in the position to say, “Can you change that?”, “Could you move that?”, you know. It wouldn’t have been good. So, very early on, it was obvious to both of us that he shouldn’t bother with this. But I said, “Hey, how about doing the covers?”, and he was, like, “Sure,” and that was great. And then I think someone at Marvel… I wasn’t that familiar with Guy Davis’s work, but someone at Marvel recommended him. And once I saw his work, I really liked it, and he was a great pleasure to work with.

COMICGATE: Well, I’m glad you did the book, because that’s how I discovered your work…

JAMES STURM: Okay, good.

COMICGATE: …and, after your lecture yesterday, it occurred to me that superheroes aren’t actually that far out, in terms of your work… I mean, in your America trilogy, you did faith, and the gold rush, and baseball, which are all very American themes, and superheroes are another very American genre…

JAMES STURM: Yeah, I love superheroes.

COMICGATE: …so it’s not as jarring as it probably seems to most people when they think of your work.

JAMES STURM: No, I’m actually working with another artist right now doing a science-fiction story, and part of that is inspired by my love of early Marvel comics and my childhood ‘70s. In it, you know, people have super-powers, and it’s fun to work on. It’s still kind of in development right now.

And, with that, my watch told me that it was two minutes to three—time for us to re-emerge from the depths of the Künstlerhaus, so the fans standing in line and waiting for signatures and sketches upstairs wouldn’t have to be kept waiting. Suffice it to say, James Sturm was right on time.

SOURCES:

- Bishop, Eli. „Bearing Witness: An Interview with James Sturm.“ du9, May 1999

- Mautner, Chris. „James Sturm Heads to the Market.“ Comic Book Resources, February 2010

- Sobel, Marc. „Sobel on Market Day by James Sturm.“ The Comics Journal, May 2010

IMAGES:

- Market Day and James Sturm’s America: James Sturm/Drawn & Quarterly, 2010/2007

- Fantastic Four: Unstable Molecules: Marvel, 2003

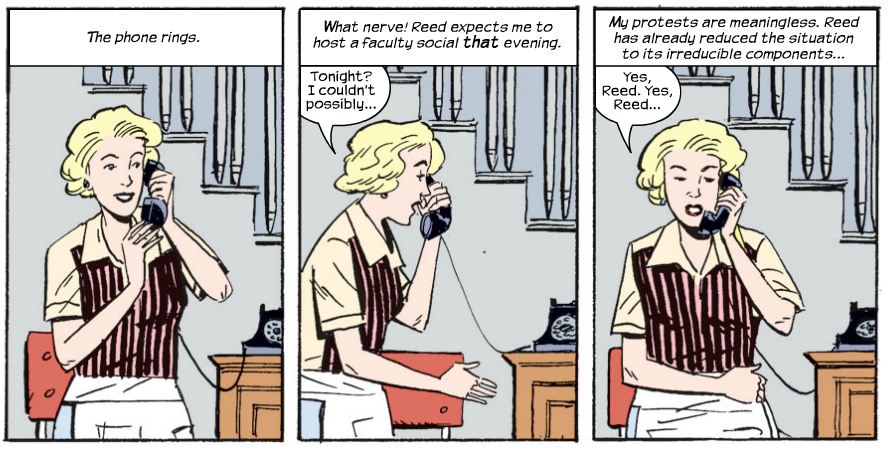

- Excerpt Fantastic Four: Unstable Molecules: written by James Sturm, artwork by Guy Davis, colors by Michel Vrana, letters by Paul Tutrone